Ten things I've learned in the last ten years (or so)

According to an old theory I built upon in my twenties, life is about reaching a series of milestones. Usually, they'd take ten years or so.

The first time I thought about it, I was 19. I decided I was already in the first stage. I'm about to turn 30.

So, what did I reach? What were my goals back then? What have I learned so far?

Disclaimer ☁️

This article covers aspects of mental health. Please don't take my advice as a substitute for professional help. If you find yourself struggling with something similar, don't hesitate to look for it.

Don't be hard on yourself

Let's go back to a kinda-distant past called five years ago. I published a post, speaking for the first time about recognising myself being bisexual.

While the article is still heartwarming and moving, I'm not that proud after rereading it. Why?

First and foremost: Fuck! I sucked at writing. Still do. But less. And it's only been five years. Granted, I didn't have a writing companion (like Grammarly) back then, and I've always lacked a decent vocabulary in English. But heck, I'm better than this at writing.

Secondly, that's the most important thing: I was brutal with myself. Not brutally honest, but brutally harsh.

Although well-founded, the "suck at writing" argument is part of me being hard on myself. That's still a work in progress.

Admittedly, I was way too soft, contrasting with how that 19-year-old me would be.

Damn, I bragged about being a horrible person to me. What a dumb thing to do.

No wonder I worked above my physical (and sometimes mental) capacity for years, to the point of being burned out (a story for later) more than a couple of times. No wonder I've been burdened with anxiety all these years.

A couple years ago (yes, this post is the work of a decade, don't mind me), I watched a video from a psychiatrist explaining why "gifted kids" actually have special ed. needs and how it relates to later life anxiety and burnout.

The reasons behind the first part blew my mind. It is not because they have cognitive difficulties, nor do they have issues with communication, but:

- Since things come off so easy for them in the first stages of life, they end up with absurdly high confidence,

- Therefore, they tend not to build habits —more importantly, study habits— which play a significant part in building a successful career later in life.

This increases because adults usually encourage that unusual lack of hardship by excessively praising children. And reinforce that confidence.

Meanwhile, people around them build high expectations. Those are transmitted to them. And grow over time.

So, there'll be a gap between the expectations around them and the skillset they have to build upon these. And the higher the expectations are, the bigger it is.

Consider that versus how easily others reach their expectations, since they are more achievable, and they are usually better prepared to do so, the outcome is that, for "gifted kids":

- They become perfectionists.

- Over time, the lack of discipline and study habits become evident. These make the complexity of studying to achieve "big goals" increase. That leads to frustration.

- Making comparisons with other people becomes more usual. Anxiety and depression tend to appear.

- Remember the expectations gap? That turns into a form of shame. The "I'm not good enough" shame. Let's call it a "gap shame".

- Take the above. Sum it up. There you have a person slowly burning out.

As a former "gifted kid" —with an IQ of 131, I can brag— I can totally identify with that. Especially with the consequences of perfectionism and that "gap shame".

Another checkup with my psychologist showed me that I needed to work on self-compassion —not the same as being self-indulgent— to start overcoming that anxiety.

It turns out that this is the first step: accept who you are and what you're capable of.

The following steps are taking things one step at a time. Push yourself. Get out of your comfort zone. It's the only way to grow.

But don't beat yourself. That is not the way.

I've been working on it for five years already. And until recently, I'm starting to get it.

Sometimes I still fall tempted to be overly judgemental of my milestones. And undermine them. But then, someone around me reminds me how far I've gone.

I hope to be, ten years in the future, that person who reminds me that I've gone places and I'm not obsolete like I used to tell myself in my early 20s.

No good comes with perfectionism

As mentioned earlier, the other part that comes with being a "gifted kid" is that you tend to be a perfectionist.

Over time, I've learned that there are no benefits to being a perfectionist. Instead, all you get is endless suffering.

Also, perfectionism is your enemy when it comes to delivering on deadlines, working under pressure —things that are pretty common in the tech industry—and making it to narrow-scoped solutions.

There's no such thing as achievable perfection. When you "finish" a piece of work, you're not getting it over, but you're just abandoning it. And that's, by definition, the opposite of perfection.

So, what usually really happens inside the mind of a perfectionist? It's a matter of wanting to make the greatest thing ever, even though you know it might take an indefinite amount of time with resources and skills you probably don't have.

Like envisioning creating an interactive game where you just wanted to develop a dice-guessing match that could have been a couple prompts. Or how you tried to create a whole stock and product line system for a company that just needed an online store.

Or you were thinking about making your manifesto: a book that defines you and your thoughts, when it is a series of articles that, together, form. Or even picture yourself working on an incredible drawing when you need to gain basic painting skills.

A couple weeks ago I asked ChatGPT to roast me. Not to beat me up, but for fun. I had a couple laughs, of course. But damn it, I found out I'm still on the works of figuring this part out.

Starting is the easiest part. Ideas are free, and talking about them is pretty cheap.

The tricky part comes when you hit yourself on the reality wall and start figuring it's too big to get it all at once. Or even worse, you're stubborn enough not to realise you're hitting over that wall time over time.

Thus, you'll never finish because either:

- You don't have the skills to build those things in the first place, and you have to overcome lots of learning and challenges before; or

- You get burdened with anxiety because the monster you initially envisioned —now that you realise your limitations— is too big to tackle.

While the first one is easier to handle since it involves learning over time, you must also learn to accept your imperfect works and appreciate how your art improves.

The real problem here lies when you commit yourself to something you're incapable of, nor are you aware of where to start.

"Fake it 'till you make it" is an infamous industry motto. And while it's generally good advice about not quitting just because you don't know, it's terrible for a person comfortable with faking it… too much.

The third thing that comes out bad when trying to be a perfectionist is this:

You can’t finish if you always restart. pic.twitter.com/Yxj2XSrVlJ

— Janis Ozolins (@OzolinsJanis) January 5, 2023

Repeating yourself, just because you haven't done perfect.

It's not unusual for people starting a learning process to reach a point where they find themselves with some of their recently acquired knowledge that needs to be polished until they are ready to go on. This is especially true for perfectionists.

And while, in theory, it's an excellent idea to strengthen your basics in any knowledge area, the reality is that you don't do it by reviewing the topics over and over but with practical experience. The one you get by doing. Otherwise, the only thing you're doing is slowing down your learning curve. Usually, some concepts might be weak at first, but as long as you keep going back on them when needed, you don't need to repeat a course twice or thrice.

It happened to me. In retrospect, this slowed down my learning curve to a point where I could have gotten enough experience creating digital products before college. Instead, I forced myself to repeat myself repeatedly in such a way I was still pretty junior by my first year in college.

It took me five years to gain the equivalent experience any other professional in my area gets in one.

But it gets worse. In the real world, the consequences are much more problematic. They might vary, but usually, they might be unmet deadlines, work delivered with poor quality results, unfinished projects, or a combination of the above.

And frustration. Tons of them.

Some years ago, a friend tweeted the following:

No hay nada más cercano a la perfección que poder hacer lo que dices poder hacer.

— Galleto (@sirgalleto) July 14, 2020

"There's nothing closer to perfection than being able to do what you say you're able to"

Today, I understand this goes beyond being able to do what you say you're able to. Still, it's about accepting that as a fact and then growing from it.

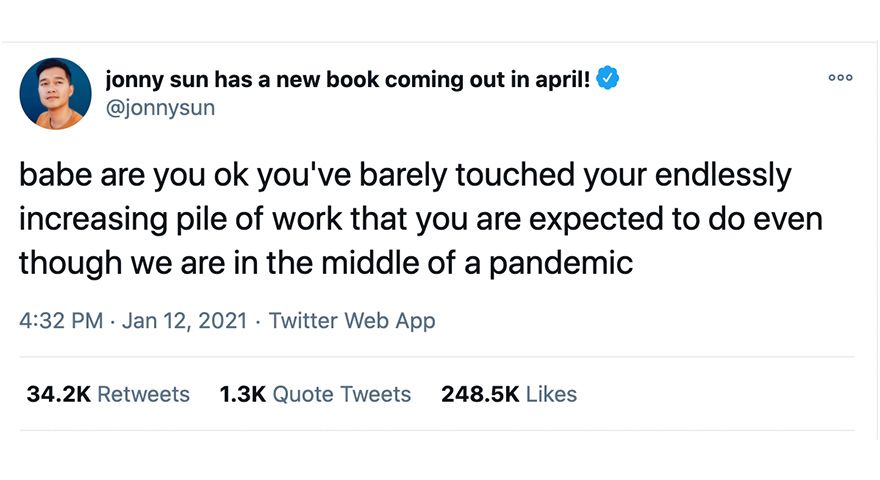

Work/life balance it's a thing. Moreover, it's necessary

Burning out is an old foe for me. I've been there more times than I could like. Thinking of it, throughout my 20s, it's affected me in many aspects I'm able to understand lately.

It's more than just the inability to respond to your studies or the projects you abandon. It's also the people you affect, the meaningful relationships you leave aside. It's your body and mind crying for help while you're in bed for a whole week, eating Domino's and watching TV series until late in the night.

Nope, I'm not talking about depression. It looks similar in appearance, but in my case, it was more related to anxiety.

Oh, and it's the procrastination. It's always procrastination. Or is it the increase of it? Good question.

I'm writing another article about how I overcame my most recent burnout, so I won't go deep into details (I promise the backstory is interesting).

But, long story short:

- The more you over-commit, the more you procrastinate, the more you fail, and the guilt will be more tremendous.

- The less you'll be able to do stuff. And the less you control your work/rest periods (throughout that article I said earlier, I focused on creating a framework for building cooldowns), the more exhausted you'll feel every other morning. And back in the loop.

- Take that, and add to other issues, like anxiety —sorry, it's been a constant all these years 😅— or depression. You'll be down on the road to inaction.

Right, burnout is terrible and all that shit. So, how do I manage it?

Sorry to disappoint you. There is no size-fits-all response. It's primarily up to you. But here are a couple of tricks:

- First and foremost: consider taking a break. Especially if you're feeling burned out, if so, stop right now. Trust me; your projects can wait. Your health can't.

- You must identify what causes it. Once you've done that, you need to take your time to prioritise your things. Remember, something that might seem important to you might not necessarily be healthy—for example, not sleeping enough, having bad sleeping habits, or working excessively because you need to cover a learning curve.

- Learn to identify when you're starting to feel burnt out. And when you are, pause and analyse the situation that created it. Then, make an honest attempt to change it.

- Some people might benefit from meditating. Personally, meditating didn't help me at that time as it helped forced me to take vacations. But as I said, no magical solution works for everyone.

Then, iterate. Getting out of the burnout spiral is not a one-move moment in your life. It may take months or even years to handle it. Also, it will not happen to you once in your life.

Finally, burnout is a necessary evil. From time to time, we need to push ourselves to see how far we can get. If we didn't, progress would be years away from our life expectancy. Being impatient about the future is part of being naturally curious. Burnout is just the signal telling us we must stop looking at the big picture and start enjoying the journey. At last, is all that effort worth it if we're not truly there to contemplate the results?

The only right pace is your own

If I had a dollar for every time I've heard people tell me I'm late in life: late for getting a degree, late for buying a house, late for…

I don't think I'd be rich but could afford a nice trip abroad.

As someone who once dropped out of college to follow his dreams, I'm familiar with those comments — and they hurt.

They hurt because they usually come from people you look up to or those you love. Parents, partners, teachers.

That's an added hurdle for you. You're not achieving enough, and you're not fast enough. Someone's son just graduated and got a job at a bank or the government.

Flash news: life's not supposed to be a single straight path; everyone should follow the same way.

Some people have kids before graduating, and their lives are pleasant. People never graduated from college: they found such a good idea that was enough for them to live off it. Others didn't even attend college in the first place: they just found a well-paid job with skills they got in the way and are self-taught.

Other people never bought a house; instead, they have millions in their pockets, so they can afford to live in a different hotel room every night, which doesn't necessarily mean they're homeless.

So, you're late for what? You live your own life. Your destiny and how you navigate this world should be in your control and not in others.

And travel abroad. That's a piece of advice that works for everyone, regardless of their path.

Fear of failure is useless*

This wouldn't need too much explanation. If none at all. But still, here we are.

I became aware of my mortality first when I was nine. And for the last 20 years, I have lived with the fear of failing, living under a bridge, and dying as a natural consequence of that failure.

I was 18 when I first pronounced a series of sentences that would become axioms for my life:

- Respect is a meaningless concept. Especially when confused with authoritarianism through fear.

- There's no such thing as absolute truth.

- Sometimes, what looks like a wrong decision takes you to the right road.

Note: this is my own experience, and that last assertion might vary. So, it's important to have some criteria around what sounds like a bad choice, despite what I've just said. 😅

It took me literal tears and therapy to fully understand that last one.

So, here's my learning: while fear is a fair signal that something wrong might happen to you, it's not necessarily true. There are well-founded fears, irrational fears, and fears that hide something else.

In my case, it was more of the latter. Fear of failure was more a fear of being seen as a loser.

But again, a loser in which sense? Even if an implausible scenario happens, I'm so out of luck I can't find options to keep living out of my current career, and I have to start again from scratch: is it a failure? Or could it be a combination of events out of my control?

So I won't be a loser. Checked! What's next?

Fear of starting again? Sure! That does exist, and it's honestly more rational. I wouldn't die due to failing, either.

I've also seen plenty of people fall and begin again. In this case, some conditions might make your journey more manageable: have a strong support network (family, friends, people who care about you), enjoy doing new things, and learn to live with the minimum.

Remember: You'll be fine.

So, what's left?

The biggest question —no doubt— is: "What would I learn if the failure were due to reasons in my control?"

Having the disposition to learn from every possible failure you have had in your past is crucial for not making it again. This is not to say you should become more averse to taking risks, but you would be wiser when taking them in the future.

While bad habits (or lack thereof) are especially more challenging to overcome, it's not impossible

You might not believe me, but I'm a recovering addict.

Remember the frustration gap I talked about earlier? Well, I wasn't aware of it. Still, in my late 10s and early 20s, as I was hitting the wall for the first opportunities in my life, as I had my first failures, that feeling started becoming more and more burdening.

But instead of tackling those issues like an adult (I was a kid, anyway), my response was to avoid them and, instead, find a hideout in food, specifically sugar.

I started sleeping less to compensate for the excess sugar in my body. Also, it felt natural to stay awake overnight so I could advance more on my projects and because I needed to dedicate more time to study since I lacked study habits and ended up distracting a lot.

My usual routine was a midnight trip to Oxxo (a convenience store) to get some Mountain Dew, Doritos, and a tube of condensed milk to help me stay up until 3 am or 4 am.

Don't get me wrong: it wasn't torture to me. I enjoyed it. I considered it a valid lifestyle for years.

But, truth be told, it also affected me in a way I didn't see until years later.

So, burnout came. We've briefly discussed it and talked about finding its causes. Well, here you got the main reason for it.

But that's not everything.

Overweight came. And then obesity. I'm still struggling with its consequences. For some, I'll have to live with them for my entire life while I can work others out.

But that's just an example of how bad habits can cause damage in the long term and even worsen other issues (see burnout and anxiety).

But… wait, is that it? Of course not!

I also learned that bad habits are merely a mask for issues hidden underneath. In my case, a combination of factors (emotional, financial —we'll talk about it later—and identity-related) made it harder to focus on tackling these bad habits.

Once you start eliminating them, it is like cutting layers off an onion: getting to the core is easier. Eventually, once you get to the core, these unhealthy habits should be more visible, making them easier to understand and work around.

So, bear with me for a while. Maybe in a year or two, I can tell you how I overcame some of those bad habits.

Appreciate your family (both given and chosen)

While this learning should be the most straightforward by far, trust me, it's not.

I grew up in a very loving family. This normally means you'll grow into a well-adjusted human being, loving and caring for others, right?

Probably, but in my case, love led to things happening:

My loving family struggled —in many cases— to shell me out of some awful stuff I should have been aware of, like not understanding that families are not necessarily unconditional, imperfection exists, and internal struggles might happen.

Tied to this, remember what I told you before about the "expectations gap"? It all starts with family.

As a consequence, for years, I felt I couldn't be myself. I had to act as this well-behaved guy who was up to the expectations put on him. That sucked.

So… I kind of developed a weird degree of apathy towards my family. Don't get me wrong: I love them, but I was really ungrateful at some point and treated them in a more transactional way.

Continuing with this story, it's no wonder I was eager to leave the nest as soon as possible. There were other reasons, too (I hated my hometown's weather, education, opportunities, and a bit of a search for independence).

I enrolled at my first university and started meeting great people, discovering new ways of living, and I was quick to break cultural burdens of where I come from.

We'll call this period the rebellion. Low grades, a progressive lack of interest in what my family thought about my future and career, and a wish to go even further with my independence and develop my career. I dropped out, partly because of that desire to build my career on my own terms and partly because I hated the bureaucracy and hatred for the education at that university.

And here's where I started meeting this chosen family. People I cherish with my heart, people I'm sure (to some degree) will be there for me, and I know I will be there for them.

To be fair, even though I felt alone, that was never true. My family was always there for me, regardless of how meanly I would treat them in response.

Finally, as the years have passed, I've grown more mature. I've had the chance to come to terms with that part of my life, accepting I can be myself around my family without being judged or having to fulfill certain expectations.

Maybe some of that was always in my head, or maybe not. I'm not in the mood to figure it out; I just accept it as part of what happened and learn the lessons for the moment when I have a family of my own.

And after that, I could start appreciating them for what they've done for me and for being there, even when I felt the loneliest.

So… appreciate the people around you. Some people have both families (given and chosen), others only have their chosen ones. Either way, it's always better than having no one around you, and that support network is invaluable.

YOU ARE FUCKING VALUABLE!

Ten years (and a half) ago, I was staying late in the office where I was working, past midnight. I was used to that, especially since I've been a night owl since I was a kid. But this time was different.

I wasn't aware of this then, but it was late at night, on the weekend, and I was working for someone else.

I didn't have a solid promise for shares on that company, nor the salary was somewhat good. Not even gonna lie: the "salary", if you can barely name it as such, was miserable —at least, for the standards of software engineering—.

But I was young, and hand't really seen that much in my entire life.

So, on many nights like that, I struggled to finish a project that, honestly, wasn't worth that much.

It's not until now, while I'm writing these words, a few blocks away from that office, located near a very popular nightlife neighborhood in Bogotá, that I notice what I missed those nights: some part of my youth.

I missed nights I could have perfectly spent with friends, with my SO from that time, with my family, studying and learning for the sake of it.

And all that wasn't very worthy. I found myself a week later begging my "boss" to let me finish the project, even accepting to divide the scraps of "salary" I accepted to receive in the first place (spoiler: I turned down the project and was never paid a single fraction of those miserable fees I was initially offered).

With that, I learned two lessons:

- ALWAYS sign a contract. Always. Even if you have absolute trust. Always sign.

- When you work for others, consider you are giving out your time in exchange for scraps. No matter how much you earn, it's always nothing compared to what the person who hires you is potentially getting. Even if you're getting shares, it'll still be potentially less.

So, make sure that those scraps help you grow. Or at least make sure to work on something you genuinely believe in.

It's finances, my friend

⚠️ Serious disclaimer here

This section is NOT financial advice, and you shouldn't take it as such.

Have it as my personal experience, and learn from my takeaways, but always consult a financial expert before taking decisions.

This story begins in the now-distant year of 2016. My main New Year's resolution for that year (conveniently written in a journal I don't have anymore) was simple yet challenging:

By the end of this year, I should be financially independent.

That's it. Not even owning a house or a car. Not nearly being there making millions. Just being financially independent.

Spoiler alert… it took me four years, a breakup, two failing companies, and a series of small loans my mom kindly gave me to start being there.

But my headache was just beginning.

A very basic skill every person should have by the time they're young adults is financial education. I lacked it.

So, long story short, it took me the last three years to make up for the mistakes I made in those first years.

I'm now going to enumare the lessons I learned to keep it short and simple:

- NEVER spend above your capacity. Some simple rules like 50/30/20 must be always on your head. But the essential is that your yearly income should never exceed your yearly expenses.

- When your salary increases (as if often happens on the first years of a tech worker) don't immediately increase your cost of living. 50/30/20 is a minimum, not the goal. Ideally, it should be 30/30/40 (with 20 out of those 40 being a savings fund, also note how that second 30 is a must because you're still a human being with needs™).

I was very unlucky, and had lots of salary instability. And because I quickly increased my cost of living a couple time, I'm still paying for those gaps, in the form of credit card debts.

Don't do that. - In line with the above, create a savings fund. It will be there for so many incidents, like losing your job, or being unhealthy and not able to perform it.

Because I didn't have a savings fund, a couple times my salary was held (because international transfers) or lost my job for some reason, I suffered.

Ideally, that fund should cover for your average of unemployment time, plus 25%, and should be the three times average of your unemployment time if you have some sort of long term investment or financial responsibility —like a mortgage, or you have children—. In my case, that is two to six months. But it varies. - But before you create that fund, pay up your debts. This is somewhat controversial, because experts would indicate you to do both things at the same time.

Here's my takeaway: compound interest works both ways. If you have lots of debt, paying up interests will be the largest part of it, and you don't want that.

Savings help, but you need to escape from that black hole before you're beyond event horizon (a.k.a. the point of no return), after which you'll be in a situation where you'll have to restructure your debt or declare yourself in bankruptcy. Ideally, you don't want that.

So, if you're in a point of certain high income, pay up your debts as quickly as possible, if your in a point of stability, create a savings fund. If you're in a point where both things happen, do both.

That's it. Hope it was useful.

Don't lose hope and keep the optimism

As we're reaching the end of this post (4,900 words to this point), I need to remember what's held me on the ground for the longest. I'm extremely hopeful and optimistic about the future.

Weird coming from someone who's struggled with anxiety in the past, and has had so many challenges to overcome, but one of the activities I prefer the most in this world is seeing the first sunrise on New Year's.

And there's an explanation for that: the first sunrise is basically a quick view to the future. And I can tell you, it's bright.

It may not seem like it throughout the year, as events happen and you get tired of some things, but if I look at it in retrospect, by the end of these ten years, the learnings I've had, as a consequence of those events are living proof that I'll be fine, and the future will be great.

Final note: it took me three years to complete this post. It's deeply personal, and comprises a series of valuable learnings like not so many people would. You better appreciate it. 🥹

A couple of thanks to the people who's read it throughout these years, to those who have given me suggestions and notes on specific sections, and highlights on those disclaimers.

Nota en español: me tardé tres años en completar este artículo. Ténganme la paciencia, pronto saldrá su versión traducida al español. 😅